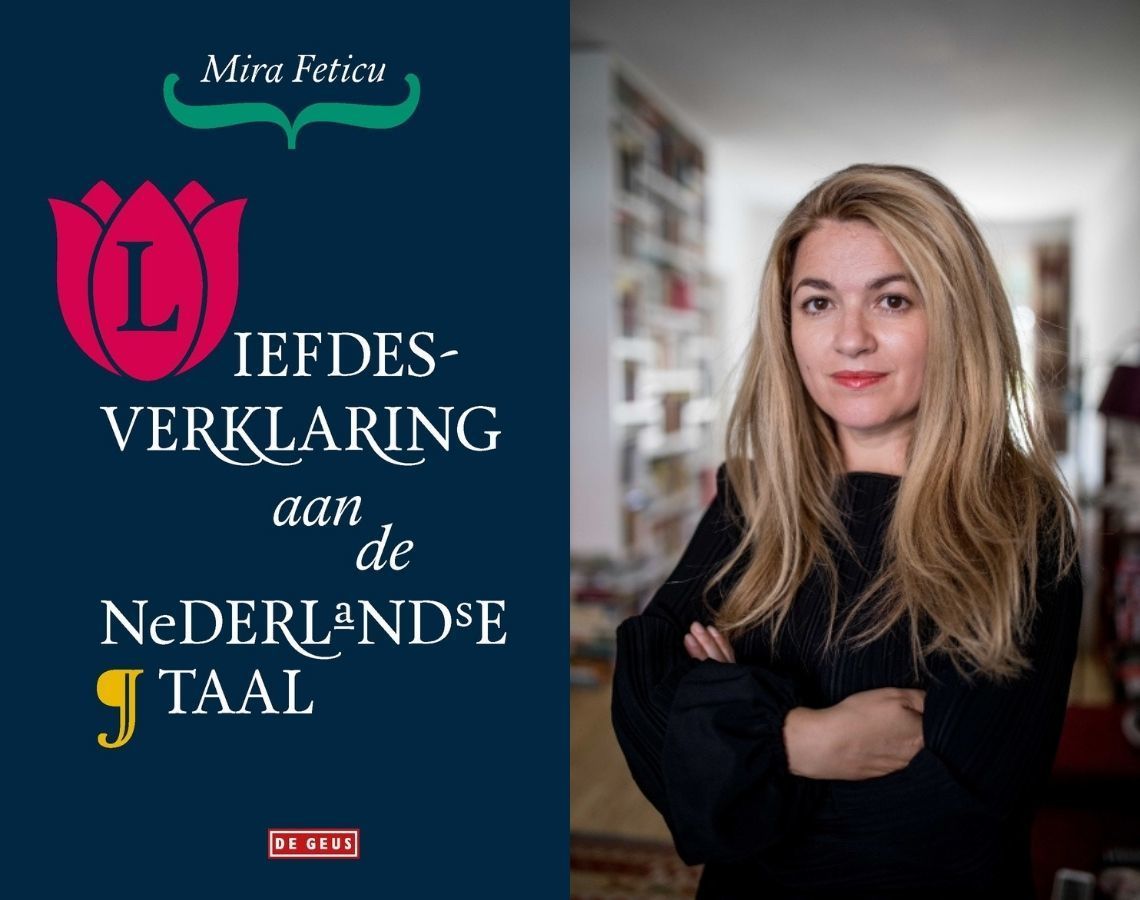

How Romanian Writer Mira Feticu Made Dutch Her Own

It requires a great deal of courage and persistence to make a new language and culture your own. In her book Liefdesverklaring aan de Nederlandse taal (Declaration of Love to the Dutch Language) Mira Feticu describes this struggle – this process of falling over and getting back up again – with Dutch. Because they are familiar to all newcomers, we had a few excerpts translated.

© Irwan Droog

p. 10

‘With the courage that comes only to the desperate, I have grasped onto writing and a new language in the way a shipwrecked sailor clings to a wooden board. The storm of emigration, the earthquake of changing geographic place, the drowning in the fear of ‘what now?’, ‘what am I doing here?’, ‘how do I go on?’; all of this was somehow lessened by language and writing: made milder, softer. Writing as a denial of loss. The text as a fetish. Leaving the words into which you were born behind is to step back, take distance; but I wanted just the opposite: to begin again. I wanted to fight on, not give up. Because letting go of words is letting go of everything. When reality takes away your dreams, only words will return them to you. This is a book written in a loneliness of the kind that I haven’t experienced since my student years, partly owing to covid, partly to myself. I was not born into this language, and neither was I four or five when I came to The Netherlands; I don’t belong to the second-generation migrants who are making it in this country, I am an eastern European who came to The Netherlands for love and who wanted to make Dutch her own. My innate urge to seek out loneliness has only been strengthened by my compulsion to make it, to skip stages, to refuse to suffer that lot. Avoiding that lot is the fulfilment of it.

Sometimes non-fiction books have an embarrassing honesty to them. This is one such book.’

p. 22

‘I dared take the leap, as always. I chose insecurity, the path of the individual. I better myself, I practice and dream of the virtuosity of a violinist, but alone my chances of survival are slimmer. I fall outside of all groups. The self-isolation for which I sometimes scold myself is the true Sisyphean task, not the learning or succeeding; it is hard, even incredibly hard, work. The last two weeks I haven’t even been working hard, all my energy has gone to fighting loneliness, a loneliness I wake up with and go to bed with. A mute scream into silence just like the one Munch has captured as an image. Worse in times of covid. The isolation is entirely my fault. When the country of your heritage and the country to which you have emigrated are two bodies that intersect, where on that line of intersection am I? And what binds us, those of us that live on that intersection? The fact that we buy food at Albert Heijn? Or the language? Not all immigrants know the language of the country that hosts them. So it is not the language, but the territory that binds us. The geography. The fact that we are forced to remain within the territory of our adopted country.’

p. 41

‘I have so often had people tell me that I have a thing for languages that I am tired of denying it. I don’t have a thing for languages. According to some, the thing for languages is located behind the eye-sockets. With me it is no different than it is with others. I don’t learn more easily than other people. But I had a strong will, I wanted to have a life here, a life in which the Dutch language would flow like the water in the Vliet. If you wake up in The Netherlands, then Dutch words are quotidian. I look out of the window and see a singel, and people taking their labrador for a walk alongside it. A huge willow. If I looked out of the window in Bucharest, I would see a church and the tram. The singel here was a singel since its first day. I can see it and get as close as possible to it by calling it a singel and not a canal or something, as in Romanian. After fifteen years here it all seems so normal; this is how things should be, the singel is a singel and the willow is a willow.

p. 78

‘When you emigrate, your first thought is not that you are leaving behind your language. Your mother tongue is just as organic as one of your arms, and you don’t leave your arms behind, do you? It is a process, not a decision made at any particular moment. You have fewer and fewer Romanians around you. And when you meet fellow Romanians, they don’t automatically become your friends. They’re nothing like your old friends. You notice that language isn’t the most significant binding factor, or at least not the mother tongue. The girl from Rwanda at my first Dutch school, Mondriaan, meant a great deal to me because I knew what she had been through. I preferred to talk to her than to other eastern Europeans or Romanians. We spoke French together because our Dutch was still at the stage of sign language. Once, during a lesson, I gave her a note in French and she didn’t give me one back. After the lesson, she told me that she couldn’t write in French, that she could only speak the language of Molière and Proust. I was bouche bée (my jaw dropped). It was the first time in my life I had heard such a thing.

For us in Romania, writing and speaking were one and the same thing. We learned French because we were Francophiles, not because we were a colony.

I turned Romanian off because I wanted to have a life. A relatively independent life. I wanted to be. You can’t keep speaking Romanian in The Netherlands and have the feeling that you are (present) there. You can’t live on polder land but not speak the language of the polders. Learning French in Romania, first at secondary school and then at university, was a privilege, a luxury. It was a feeling like getting a new coat or new shoes. Learning French was a kind of indulgence. Learning Dutch is a marathon.’

p. 122

‘Why did I leave my Jacob’s Ladder behind? Far from my village I was invisible until I opened my mouth, which was something I found comical, but it made me proud. Here it was the language that made me funny: my accent, my pronunciation errors or linguistic mistakes. And yet I wanted to be here, in this language. Is this a form of masochism? Is Dutch a self-wrought conspiracy aimed at myself? Am I sabotaging myself by writing in a new language? Why start again at the age of thirty-two? Where did I find the strength to make it through each phase? It begins with depression, a dark cloud that hangs above your head, because you do not understand what the people around you are saying. Do you have the strength to endure a few seasons until you can begin to hack this verbal lasagna into smaller pieces or words? Your mental itch and your physical agitation when you want to form a sentence yourself. You can do it. You tell yourself that the woman at the Albert Heijn checkout didn’t realise that you aren’t from here. How would you feel if you knew that thirty years later people would still see you as a foreigner? Don’t think about it, remember that there are people who like you just as you are, the way you pronounce the words. Your first real conversation. ‘Unbelievable how deep into the language you can go, even though you have only been here for a few years,’ somebody said to you. It doesn’t matter that it’s your psychologist, who is working with you on acceptance. ‘All of the decisions that you have made were the right ones in those moments.’ And so that includes the decision to start writing in a new language. First in floods of tears. Really? If you want to continue, you will believe anything. Even if you will never write perfect Dutch. You follow the advice of Flaubert, who compared writing to combing your hair: the more you comb, the more it shines.’

p. 158

‘When I can no longer bear the weight–sometimes, when it all briefly becomes too much and too heavy – I tell myself that I’m not just doing it for myself, but for everybody who will come after me. If you come to The Netherlands, don’t create a bubble of English around you; give the Dutch language a chance! Because the language will always give you chances in return. Perhaps some people think that I am an extrovert and that everything is easier for extroverts. That’s not right. I have never found it easy to connect with people; this is just the outward appearance of the wizard of Oz, the dazzle of the performer. Like Don Quixote, who also had no experience of doing battle with the windmill or acting the part of a knight, I too have a shield: language and my education in general. Eighty per cent of what I know I already knew twenty years ago in Romania. I am like a boa constrictor: I gulped down things there, and here is where I can use it. In another language, in another society.’

p. 180

‘Language always makes the difference; humanises. A year or two ago I fell on a zebra crossing because I was running to catch a tram. I fell onto my front, not very badly; I had a few grazes. On my left I saw cars stop to give me time to get back up. But it wasn’t the pain in my knees or elbows that occupied me there on the street, but rather an uncomfortable feeling about my body that was lying on the zebra crossing. The discomfort of having a body that is there; prone in front of a line of cars. The feeling that I should help that body get up, but at the same time the feeling that that body was not me myself. I wasn’t that plump body whose knees were visible through ripped trousers. I had to carry it, true enough, help it to its feet, but the worst part of it was that nobody in my vicinity said anything, there was no word to help me feel human again, a word through which I could become myself again: myself with a body. What occupied me there, prostrate in the street, was that everything was a silent film, not a word, not a sound: I lay there and on my left-hand side was a line of cars waiting for my body to stand up, and on my right-hand side I saw the tram that I had missed gently zigzagging its way to the next stop. It lasted for an eternity. I was part of the landscape, a body between the tram and the cars. Finally I stood up and pushed my body home. At home I was also alone, silence. That uncomfortable feeling stayed with me for a long time. Not only because I kept measuring out that distance between my body and myself there on the crossing, but because the most essential thing of all was lacking there: language. Something said to make you feel better, more than the clumsy body that couldn’t keep itself upright. Talking. Talking also in the case of maltreatment, abuse, violence. Talking, telling, coughing up, getting away from you. Being words. Only words have saved me from life’s miseries.’

p. 215

‘I started aged thirty-two, like a child pretending to be a builder. First with simple constructions of sticks and stones, and then slowly I grew up to be a real craftsman. As far as I am concerned, there is no difference between writing a column in Dutch and my columns for the radio in Bucharest. There is a difference in writing books, though: I have become better at it in Dutch. Practice makes perfect, and this is the case also for literature written in a strange language, art.

I remember the hopelessness of jumping without a parachute: the conviction that I would never be able to build a house of sufficient quality and strength to live in. It is said that simple language holds simple thoughts. But my simple language contains very complicated thoughts; in my head there was an architecture so complicated that it would stun you; a whole world that wasn’t only very high, but also deep. Especially deep, I would say. For this complex architecture of the mind I didn’t yet have a language; I was pregnant with a child that could not be born and the child became only bigger and bigger, like in that book by Pascal Bruckner, Le Divin Enfant. (…) Should I not have been pulling on the cart that is Dutch like a madwoman? Yes, had I been younger. But life is short. Foreigners come to The Netherlands and carry on with their lives. They learn to cycle or swim; they learn ‘genieten’ (to enjoy), as we say in Dutch. I stopped breathing when I came to The Netherlands, until I could form sentences in Dutch. I still can’t swim, and I only just learned to cycle during the lockdown. The Dutch language is to me what wood, stones and cement are to the tradesman. I am a builder working with the Dutch language, and occasionally, in the middle of my books, in flurries, an engineer. Someday I will be an engineer proper. Perhaps even an architect. Hopefully I will have the space to keep building and breathing. Avoiding that lot is the fulfilment of it. But my books are my declaration of love to the Dutch language.’